Academy schools are state funded schools which are independent of Local Education Authorities (LEAs), unlike ‘community schools’ which are subject to more Local Education Authority control and receive their funding from them.

Academies receive their funding directly from the government and have the freedom to manage their own budgets, fire and hire staff, set their own daily timetable and term dates and do not have to follow the national curriculum.

Every academy is required to be part of an academy trust (AT), which is a charity and company limited by guarantee. They can seek additional funding from companies, philanthropists, charities or religious organisations, and are non-profit organisations.

They were first introduced under the New Labour Government in the late 1990s and have gradually replaced schools managed by Local Education authorities.

Some academies are run as part of a multi-academy trust (MATs) such as Harris-Academies where several schools are run under one centralised management structure.

Most of the early academies chose to become academies, but some have been forced to convert away from LEA control to academies following an ‘in need of improvement’ grading by OFSTED, many of these converter academies having to choose an MAT to manage them.

Like community (LEA) schools academies are inspected by OFSTED and follow the same nationally imposed rules regarded exclusions and Special Educational Needs provision.

Types of Academy

There are three main types of academy schools: sponsored, converter and free schools.

Sponsored Academies

Sponsored academies were the first type of academy, established under New Labour in the year 2000. They are typically underperforming schools which have failed an OFSTED inspection and have been required to move away from LEA control and become academies.

In the early days sponsors were businesses, philanthropists, charities or religious organisations but today well established successful academies or MATs can be sponsors and take over failing schools.

Converter Academies

These are already existing schools under Local Education Authority control which have voluntarily chosen to become academies.

There are certain advantages to a school becoming an academy – more control over its affairs and the fact that they save on 15% VAT on goods and services which they don’t pay, unlike LEA schools.

Converter academies are the main type of academy today and account for 2/3rds of existing academies.

Free Schools

Free Schools are newly created schools which are run as academies.

Free Schools were introduced under the Coalition Government in 2011 and are typically established by local interest groups who want a better standard of education for their children.

So far they have been established by groups of parents, teachers, charities, businesses and faith groups.

A History of Academies

City Academies were first introduced in the year 2000 under New Labour and then saw a rapid expansion under both the Coalition (2010-2015) and Tory governments (2015 to present day).

Academies under New Labour

Academies were first launched as ‘city academies’ in 2000 under the New Labour (1997 to 2010) government, and Lord Adonis, then education advisor to the Labour government, is credited with their establishment.

Most early academies were ‘sponsored academies’ – they were failing LEA schools in deprived urban areas which were shut down and then re-opened under new management as academies and in the early 2000s huge amounts of capital funding was injected into these early academies.

In 2002 the prefix ‘city’ was removed to allow schools in non urban areas to join the academies programme.

The rationale behind academies was that they would raise educational standards through increasing diversity and choice and encouraging competition between schools – and they are thus an expansion of the ‘marketisation’ of education introduced by the previous Tory government.

Early academies were founded and governed by sponsors including businesses, charities and universities, with funding initially capped at £2 million per school. (This cap was lifted in 2009).

New Labour’s early academies had a greater intake of Free School Meals students and the hope was that by making them independent of LEA control and introducing private sponsorship they would encourage a culture of high aspirations among students and thus break the cycle of deprivation.

This focus on combining marketisation and social justice concerned is very characteristic of the third way ethos which lay behind many of New Labour’s policies.

Mossbourne Community Academy

An example of a successful early academy is Mossbourne Academy in Hackney, which was opened in 2004 with a capital budget of £23 million being spent on shiny new school buildings.

The first headmaster of Mossbourne Academy was (now) Sir Michael Wilshaw, who went on to become the chief inspector for OFSTED. He instigated a regime of high expectations of all students with strict rules about not only attendance and punctuality but also strict dress code.

Teachers were required to work long hours as were students deemed to be in need of extra help to reach their target grades with additional after school lessons and Saturday lessons part of the weekly regime for those who required them.

The school also set up a range of extra curricular activities emulating private schools such as a debating and rowing club – increasing access to cultural capital for those students who took up these opportunties.

Mossbourne was extremely successful in getting its students excellent grades but there is a question mark over how much of this was down to the extreme amount of initial funding injected into this flagship academy project.

By 2006 there were 46 academies established, half of these in London, which had capital and operating costs of £1.3 billion.

By 2010 there were 203 Academies up and running.

Academies under the Coalition

The Coalition identified academies as one of their main education policies for simultaneously raising standards and improving equality of educational opportunity by narrowing the achievement gap.

The Coalition government pursued the setting up of academies even more enthusiastically than the previous New Labour government, their aim being to make it the norm for all state schools to be academies, rather than just for failing schools and schools in deprived areas as had been the case previously.

The new Coalition Education Secretary Michael Gove wrote to all head teachers in 2010 informing them that all secondary and primary schools would be invited to convert to secondary school status, and schools with and OUTSTANDING status from OFSTED would be fast tracked through the process of conversion.

In 2011 the academy conversion process was extended to all schools doing well, and other schools not classified as doing well good convert to academies if they joined already existing academy chains which were doing well.

Fast tracked schools were required to support at least one weaker school, the idea being that better schools would partner with weaker schools and help them improve.

The Coalition also continued with ‘forced academisation’, in June 2011 the government announced that it would be forcing the weakest 200 schools to become academies, under new management, typically an already existing well-performing academy or academy trust.

The 2010 academies act also made it a requirement for all new schools to be either academies or free schools (see below) – this prevented the Local Education Authorities from setting up new schools.

Michael Gove also introduced legislation which allowed for the establishment of Free Schools – entirely new academies which allowed teachers, parents or religious groups (for example) to set up a new school in their own area if they were not satisfied with local provision. By the end of the Coalition government 254 Free Schools had been opened.

All through the five years of the coalition government the academies programme continued at a rapid pace – by the end of the New Labour government in 2010 there were 203 academies, and within nine months of the coalition this had doubled to 442 academies.

By the time of the general election in 2015 there were just over 5000 academies in England and Wales, which was 40% of all secondary schools.

The rapid rise of academies during the Coalition is down to two factors primarily:

- The streamlined application process made it a lot faster to convert

- There were financial benefits to becoming academies – independent control of budgets (rather than LEA control) made finances easier to manage and there was additional central funding available, all during a time of austerity which made converting very appaling.

West and Baily (2013) have suggested that while New Labour saw academies as a way of solving the problem of failing schools the Coalition used setting them up en masse to enact system wide change towards a more marketised education system.

Academies since 2015

When the Tories came to Power in 2015 David Cameron’s stated aim was to achieve full academisation, that is he wanted ALL schools to become academies.

A 2016 white paper proposed that all schools had to start converting to academies by 2020 and that any that hadn’t would be instructed to do so by 2022, the idea being that the Local Education Authorities would have no role in management education by 2022.

However, there was resistance to this forced academisation, especially by primary schools which were doing well and were reluctant to hand over control to relatively new Multi Academy Trusts and these plans were relaxed and the government focused its efforts on ‘encouraging’ LEA schools to convert voluntarily rather than forcing them.

Even so the number of academies continued to increase rapidly under the Tory government and by 2020 the number of academies had risen to over 9000, an increase of around 1000 per year, and most of these converter academies.

There are also new national structures in place now to regulate academies:

- The Education and Skills Funding Agency regulates funding

- The Schools Commissioners Group made up of eight regional commissioners for schools monitors academies in their regions.

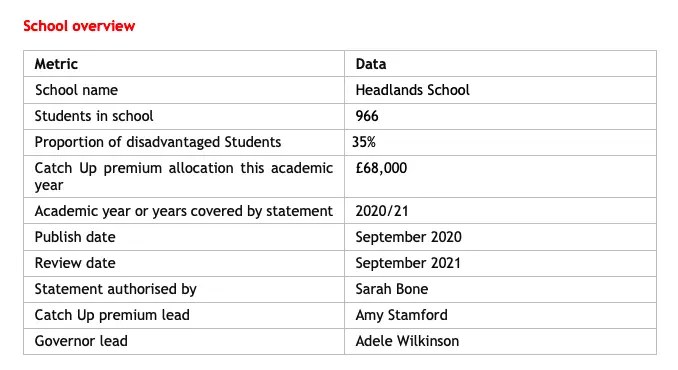

The growth of Academies in England and Wales

The total number of academies in England and Wales has grown rapidly since 2010, although the rate of growth has slowed in more recent years.

- In 2009 to 2010 there were a total of 133 academies

- By 2019/ 2020 there were a total of 9200 academies

The total number of academies increased by 5% between 2018/2019 to 2019/2020, but this figure would have been lowered because of the impact of Covid, as schools focused on dealing with safe re-opening and helping pupils catch up rather than converting to academy status.

Key for the above table:

- Dark blue = sponsored academies

- Light blue = converter academies

- Mid blue (smallest) = Free Schools.

There are more secondary than primary academies…

- In 2020 78% of secondary schools were academies, 22% where LEA run schools

- This compares to 36% of primary schools being academies, 54% remain under LEA control.

Multi Academy Trusts

The number of schools in MATs has increased since 2018, with the largest increase being for schools in trusts with 6-10 schools, with 25% of schools being in trusts of 6-10 schools.

Approximately:

- 15% of schools are single schools

- 40% are in small trusts of 2-9 schools

- 25% are in large trusts of 10-19 schools

- 20% are in very large trusts of 20+ schools

The average number of schools in a trust has increased from 5 to 7 schools in the last four years to 2022 and the largest trust today has 75 schools in it.

Evaluations of Academies

There has been criticism of how far New Labour’s early academies managed to break the cycle of deprivation (Gorand 2009, Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2008)

Under the coalition the Local Education Authority system of provision of schooling was dismantled – this involved democratically elected bodies planning appropriate educational provision for a local area. This has now been replaced with a greater diversity of provision, increased competition between schools and greater involvement of non-elected officials (sponsors) in how local schooling is run (Walford 2014)

As a result there is now a lack of accountability to the local communities in which academies exist because there is no LEA control.

Funding arrangements for academies are agreed between the secretary of state and the management company of the academy – this means there is no ‘democratic oversight’ of funding arrangements – sponsors are effectively operating outside of the democratic process (Ward and Eden (2009).

While the government speaks of ‘diversity and choice’ another way of looking at this is that they have created a fragmented education system – when there is no local planning for provision you get overlap and inefficiencies, especially where Free Schools are concerned!

Multi Academy Trusts vary in their degrees of competence, and for those schools which are still under LEA control, they may be better off remaining so, BUT LEAs now get much less funding because so much of it has been siphoned off to the academy trusts, so they may not be able to offer as much support in the future.

In short, it’s possible that academisation has gone so far and now LEAs are so weakened that full academisation is possibly now inevitable.

Signposting and Relevance to A-Level Sociology

This material is primarily relevant to the education aspect of the AQA’s A-Level Sociology specification.

Sources/ References

Barlett and Burton (2021): Introduction to Education Studies, fifth edition

Academy Schools Sector in England Consolidated Annual Report and Accounts For the year ended 31 August 2020, HC 851

Education Data Lab – stats on academies in England and Wales.

Politics.co.uk on Academies – a useful summary of some of the Key Facts about academies.