Mafia syndicates in Italy have an estimated annual turnover of £150 billion, making it much larger than Italy’s largest holding company (which includes Ferrari).

Increasingly, it is not drugs or people trafficking which bring in the money for the Mafia, but there involvement in agriculture, or basic food production.

Today, the Mafia are invested in Italy’s food industry from ‘Field to Fork’…. their agricultural interests extend to extortion, illegal breeding, backstreet butchering and the burial of toxic waste on farmland.

In 2018 the estimated value of the ‘agromafia business’ stands at £22bn, equivalent to 15% of Mafia revenue. This may seem mundane, but think about it: everyone has to eat, and most people like to eat everyday, so it should be no surprise that this is a growth area… it’s simply where the demand is!

There are all sorts of ways the Mafia can make money out of the food business – the most obvious is counterfeiting, and it is estimated that up to 50% of all olive oil sold in Italy is cut with poorer quality oil. To do this, the Mafia makes use of its global criminal ties… cutting it with lower quality oil from Africa.

The Mafia also rebrand low quality wine as higher quality: they simply change the label.

One of the more unfortunate costs of this whole business is the thousands of workers who are currently being exploited working for Mafia controlled agribusiness. The figures are quite significant:

It’s also estimated that up to 5000 restaurants are controlled by the Mafia, which is useful for money laundering.

Up until quite recently the Mafia also used to lease huge swathes of public land and make a fortune by claiming back EU subsidies on this land, making a 2000% profit in the process: they basically used their white collar connections in local governments to make sure no one else got involved with the bidding process.

However, this final practice has been clamped down on.

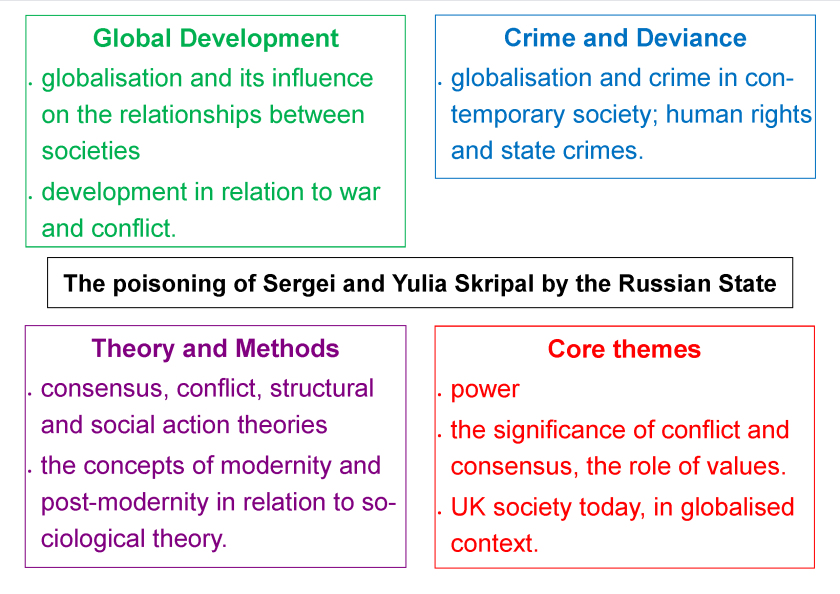

Relevance to A-level sociology

This is a useful update to the globalisation and crime, and especially to Glenny’s work on the McMafia: it shows how the Mafia are ‘evolving’ in their global criminal activities.

Sources:

Agromafia: how the mafia got to our food…

Agromafia exploits hundreds of thousands of workers.