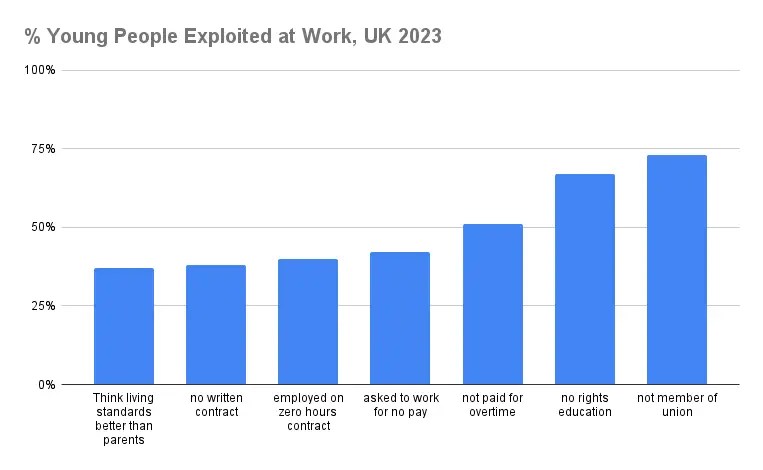

Millions of young people in the UK are being treated unfairly at work. Around half of young workers are exploited in some way, for example through being underpaid. Young people lose up to £1.65 billion each year through wage theft, and over 100,000 are never paid for overtime at all.

This is according to some recent research from the Equality Trust published in 2023: Your Time, Your Pay. The primary purpose of this research was to assess young people’s knowledge, awareness and application of their employment rights. The research was based on a sample of 1018 16-24 years olds.

Examples of how young people are exploited at work include…

- Unpaid trial shifts

- Working without a contract

- Zero hours contracts

- Lower minimum wages

- Not being auto-enrolled onto Pensions

- Lack of education about employment rights.

The rest of this post outlines the economic challenges young people face, statistics and cased studies about young people being exploited at work and recommendations about how to improve things.

Economic challenges young people face

Young people are exploited in work despite facing huge economic challenges:

- Young people suffered more from the Pandemic with school closures and higher rates of job losses. Under 25s accounted for 60% of job losses during lockdowns between February 2020 – March 2021.

- Young people face wage discrimination as employers are legally allowed to pay them less. The minimum wage for under 18s is a dismal £5.28 an hour.

- Relative scarcity of housing means rents have increased, and buying is simply out of reach for most under 25 year olds. For those who want to buy they have to save tens of thousands of pounds for a deposit.

- For those who choose to go to university, they are saddled with tens of thousands of pounds of debt.

- Recent high rates of inflation mean the cost of living is relatively higher for young people today compared to their parents when they were younger.

As a result, it is the norm for young people to face ‘financial precarity’. A 2022 report found that 47% of young people (aged 16-25) are experiencing financial precarity. This number grew as young people got older, with 57% of 22-24-year-olds in a precarious financial situation.

And yet despite these challenging times, many young people who have to work out of necessity or choose to work to get ahead suffer massive exploitation at the hands of their employers…

Young people being exploited at work: statistics

The Equality Trust report found that…

- 42% of young workers have been asked to work for no pay.

- 51% of young people work overtime, over half have not always been paid for it.

- 38% of young people either do not have or do not know whether they have a written employment contract.

- 16-17 year olds were the least likely age cohort to have a written employment contract with only 34% having a written contract. This compares to 59% of 18-21 year olds and 67% 22-24 year olds.

- 40% of young people have been employed on a zero hour contract.

- Almost two thirds of young people did not receive, or don’t know if they received, information about employment rights at school.

- 73% of young people are not members of a trade union.

- Only 37% of young people think their standard of living is better than their parent(s) or guardian(s).

Young people being exploited at work: case studies

The focus group revealed the following examples:

- Unpaid trial shifts: One worker who did a 4 hour trial shift in an expensive homeware store who made a £50 sale despite receiving no training during that 4 hours and being reprimanded for using the till incorrectly.

- Working without a contract: On person worked as an age verification checker where she went into off-licences and betting shops to see if they asked her proof of her age. She had to write detailed reports but had no formal contract. She saw the job advertised specifically to students on TikTok.

- Working as bar staff at a music festival – One respondent reported that they had to spend £40 on their train ticket to event despite being told travel costs would be paid at their interview. The agency oversubscribed workers assuming some wouldn’t turn up so when she arrived for a shift at 7.00 a.m. she was told she wouldn’t be starting until 18.00.

- One respondent reported a positive experience on working a zero hours contract for an administrative body where the flexibility was mutually beneficial.

Research Methods used in this report

The polling was conducted by Survation in November 2022 and they surveyed 1,018 young people from across the UK.

They also ran two focus groups with a total of nine young people; one to co-produce the questions for the survey and the second to analyse the results.

They ensured they sampled a diverse group of young people from a range of socio-economic backgrounds.

Recommendations

Based on the above findings the Equality Trust recommends that…

- The government should abolish the National Minimum Wage rates based on a person’s age.

- Unpaid trial shifts should be made illegal.

- Expand automatic pension enrolment to qualifying over-16s.

- Schools and colleges need to do more employment rights based education.

- Trades Unions could do more to attract younger people.

Signposting and relevance to A-level sociology

This is a fantastic example of how to use focus group interviews in social research. Focus groups really work here because they give respondents a chance to share their experiences of being exploited with their peers. By being able to listen and respond in a supportive environment this should help encourage respondents to open up. The topic isn’t so sensitive as to require one on one interviews.

To return to the homepage – revisesociology.com

Sources/ Find out More

For more research from the Equality Trust.

Citizens Advice: Check your Rights if you’re under 18.