Last Updated on February 17, 2021 by

What is the state of global education? What are the barriers to providing universal education for all, and how important is education as a strategy for international development and economic growth? Can western models of education work for developing countries, or are more people-centred approaches more appropriate and/ or desirable?

Education: Global Goals

Ensuring inclusive and quality education for all is objective number four of the United Nation’s new Sustainable Development Goals.

Four specific challenges are identified:

- Enrollment in primary education in developing countries has reached 91 per cent but 57 million children remain out of school

- More than half of children that have not enrolled in school live in sub-Saharan Africa

- An estimated 50 per cent of out-of-school children of primary school age live in conflict-affected areas

- 103 million youth worldwide lack basic literacy skills, and more than 60 per cent of them are women

Some of the specific targets for 2030 include:

- Ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes

- Ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education

- Ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university

- Eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations

However, we remain a long way off these targets:

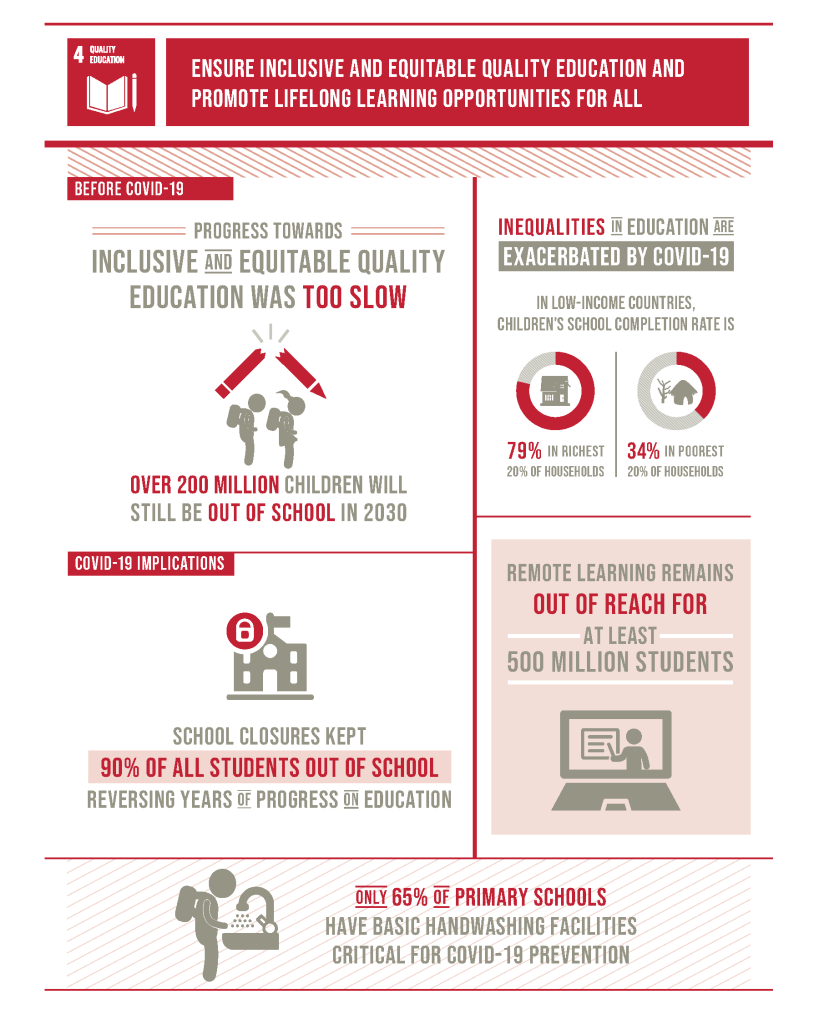

- Before the coronavirus crisis, projections showed that more than 200 million children would be out of school, and only 60 per cent of young people would be completing upper secondary education in 2030.

- Before the coronavirus crisis, the proportion of children and youth out of primary and secondary school had declined from 26 per cent in 2000 to 19 per cent in 2010 and 17 per cent in 2018.

- More than half of children that have not enrolled in school live in sub-Saharan Africa, and more than 85 per cent of children in sub-Saharan Africa are not learning the minimum.

- 617 million youth worldwide lack basic mathematics and literacy skills.

- 750 million adults – two thirds of them women – remained illiterate in 2016. Half of the global illiterate population lives in South Asia, and a quarter live in sub-Saharan Africa.

- Coronavirus has had a disproportionately negative affect on students in developing countries – as a much higher proportion lack computers to allow home education.

Education in Developing and Developed Countries: A Comparison

Looking at the global picture is one thing, but looking at statistics country by country provides a much better idea of the differences between developed and developing countries in terms of education.There are a number of indicators used to measure progress in education and just some of these include:

- The primary enrollment ratio.

- The mean number of years children spend in school.

- Attendance figures (at primary and secondary school and in tertiary education).

- Literacy rates (which can be for youth or adults).

- National Test Results (e.g. GCSE results)

- Performance in international tests for international comparisons – such as the PISA tests.

- The percentage of GDP spent on education

(The main sources for data on education come from the United Nations, UNICEF, and The World Bank.)

A selected breakdown of some of these statistics shows the enormous differences in education between countries:

| Ethiopia | Kenya | India | The UK(6th in world) | |

| Youth Literacy Rate Male | 62.00% | 82.00% | 88.00% | 100% |

| Youth Literacy RateFemale | 47.00% | 80% | 74.00% | 100% |

| Primary attendance | 65.00% | 74.00% | Male 98%Female 85% | 100% |

| Secondary attendance | 16.00% | 40.00% | Male 58%Female 48% | 100% |

| GDP PPP | $1200 | $1800 | $4000 | $36000 |

| %of GDP spent on education | 4.70% | 6.00% | 3.30% | 5.8% |

In the UK, The government spends nearly £90 billion a year on education, employing over 400 000 teachers (all of whom have to be qualified)and over 800 000 people in total in the education system. Education is compulsory from the ages of 4 to 18, meaning every single child must complete a minimum of 14 years of education, and the majority of students will then go on to another 2-3 years of training in apprenticeships or universities. In the primary and secondary sectors, billions of pounds are spent every year building and maintaining schools and schools are generally well equipped will a range of educational resources, with free school meals provided for the poorest students.

Since the 1988 education act, all schools are regularly monitored by OFSTED and thus every school head and every single teacher is ultimately held to account for their results, and the system is very much focused on getting students qualifications – GCSEs and A levels, of which there is a huge diversity. At the end of secondary school, around 70% of students have 5 good GCSEs, but even those who do not achieve this bench mark have a range of educational and training options available to them.

It might sound obvious to say it, but there is also a generalised expectation that both students (and staff) will attend school – attendance is monitored regularly and parents can be fined and even sent to jail if their children truant persistently.

In addition to getting students GCSEs, schools are also required to a whole host of other things – such as teach PSHE lessons, prepare students for their future careers,foster an appreciation for multiculturalism,monitor ‘at risk students’ and liaise with social services as appropriate. Schools are also supposed to differentiate lessons to take account of each individual students’ learning needs.

Of course there are various criticisms of the UK education system, but after 16 years of schooling the vast majority of students come out the other end with significantly enhanced knowledge and skills. Finally, it is worth noting that girls do significantly better than boys in every level of the education system.

Things are very different in many poorer countries around the world – For a start the funding difference is enormous, more than a hundred times less per pupil in the poorest countries; many school buildings are in a terrible state of repair, and many schools lack basic educational resources such as text books. Attendance is also a lot worse, especially in secondary school, and in some regions of India 25% of teaching staff simply don’t show up to work (while reporting very high levels of job satisfaction). A third significant difference is that there is no OFSTED in developing countries, and so schools aren’t monitored- teachers and schools aren’t held accountable for student progress, which is reflected in the fact that a huge proportion of students come out of the education system with no qualifications.

How Can Education Promote Development?

There is no doubt that education can promote development…

Firstly, education can combat poverty and improve economic prosperity. For every year at school education increases income by 10% and increases the GDP growth rate by 2.5%.Teaching children to read and write means they are able to apply for a wider range of jobs – and potentially earn more money, rather than being limited to subsistence agriculture.

Secondly education can be used to improve health.School can be used to pass on advice about how to prevent diseases and thus improve health and they can also be places where free food and vaccinations can be administered centrally (as is the case in the UK) – improving the health of a population.

Thirdly, education can combat gender inequality.This is illustrated in the case study of Kakenya Ntaiya, who, at the age of 11 agreed with her father that she would undergo FGM if he allowed her to continue on to secondary school, which she did, eventually winning a scholarship to study in the United States. There she learnt about women’s rights and returned to her village in Kenya and set up a girls only school where currently 100 girls are protected from having to undergo FGM themselves.

Fourthly, education can get people more engaged with politics. You need to be able to read in order to engage with newspapers and political leaflets and manifestos, which typically contain much more detailed information than you get via radio and televisions. Thus higher literacy rates could potentially make a country more democratic – democracy is positively correlated with higher levels of development

Barriers to Providing Education in Developing Countries

There are many barriers to improving education in developing countries which means that development through education is far from straightforward…

Read the section below and complete the table at the end of the section.

Firstly, poverty means that developing countries lack the money to invest in education -this results in a whole range of problems – such as very large class sizes, limited teaching resources, a poor standard of buildings, not enough teachers – let alone the resources to monitor the standards of teaching and learning.

This is well illustrated in this video of Khabukoya primary school in a remote region of Kenya, near the Ugandan border.

Kenya spends 6% of its GDP on education and has a comparatively good level of education for Sub-Saharan Africa – yet this school appears to have been forgotten about. The school has 400 students and yet only one classroom with a concrete floor and desks, with all other classrooms having mud floors, and being so small that students are practically sitting on top of each other. Funding is so limited that the school relies of volunteer labour to partition the too-few classrooms they have, a task which is being done with mud and water, and to make matters worse half of the students are infected with jiggers, a parasitic sand flea which burrows into the skin to lay its eggs, which causes infections which are often disabling and sometimes fatal.

Secondly, the high levels of absenteeism in primary and especially secondary schools is a major barrier to improving literacy. Most developing countries have enrollment ratios approaching 100%, but the actual attendance figures are much lower. Even in India, a rapidly developing country, the female secondary attendance rate is 50%, while in Ethiopia, it is down at 16%.

Thirdly, the persistence of child labour– The International Labour Organisation notes that globally, the number of children in labour stands at 168 million(down from 246 million in 2000) and 59 million of these are in Sub-Saharan Africa.Agriculture remains by far the most important sector where child labourers can be found (98 million, or 59%), but the problems are not negligible in services (54 million) and industry (12 million) – mostly in the informal economy.

Fourthly, poor levels of nutrition in the first 1000 days of a child’s life significantly reduces children’s capacity to learn effectively – malnutrition leads to stunting(being too short for one’s age) which affects more than 160 million children globally and more than 40% of under-fives in many African countries including Somalia, Uganda and Nigeria. According to the World Health Organisation children who are stunted achieve one year less of schooling than those who are not.

Fifthly, War and Conflict–The United Nations notes that 34 million, or more than half all children currently not in education, live in conflict countries, making conflict one of the biggest barriers to education. Many of these children will be internally displace refugees, but on top of this there are approximately 7 million children living as refugees in non-conflict countries (stats deduced from this Guardian article) and most of these receive a poor standard of education. In conflict countries, the vast majority of humanitarian aid money is spent on survival, with only 2% going towards education.

One of the most interesting examples of conflict preventing education (at least ‘western education especially for girls’) is the case of Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria– A terrorist organisation who gained international notoriety in 2014 when they kidnapped 200 girls from their school dormitory.

Sixthly, Patriarchal cultural values– means many girls the world over suffer most from lack of education.Pakistan and India are two countries which have significant gender inequalities in education provision – In India (one of the BRIC nations) the percentage of girls attending school lags 10% points behind that of boys, a situation which is even worse in Pakistan, the country is which Malala Yousafzai was shot by the Taliban for attending school. In this video she describes some of the fear tactics the Taliban use to prevent girls going to school – such as bombing schools which allow girls to attend and public floggings of women who allow their daughters to attend school.

Although the starkest examples of gendered educational opportunities are to be found in Asia, there is also inequality in Africa and this blog post talks about gendered barriers to education in East Africa

A seventh barrier is the lack of teachers to improve education –the link has a nice interactive diagram to show variation by country.Somewhat ironically this link takes you to an article which discusses how increasing primary education has led to problems as this has led to an increase in demand for secondary education – which many African countries are too poor to provide!

Finally, an eighth barrier is widely dispersed populations in rural areas means children may have difficulty getting to school.

Is a Western Style of Education Appropriate to Developing Countries?

Many of the education systems in developing countries are modelled on those of the west – in that they have primary, secondary and tertiary sectors, they emphasise primary academic subjects such as English, Maths, Science and History and they have external systems of exams which award qualifications to those who pass them. The idea that a Western style of education is appropriate to developing countries is supported by Functionalists/ Modernisation Theorists and generally criticised by Dependency Theorists and People Centred Development Theorists.

Functionalist thinkers (Functionalism is the foundation of Modernisation Theory) argue that Western education systems perform vital functions in advanced industrial societies. These functions include (a) taking over the function of secondary socialisation from parents (b) equipping all children for work through teaching a diverse range of academic and vocational subjects, (c ) sifting out the most able students through a series of examinations so that these can go on to get the best jobs and (d) providing a sense of belonging (solidarity) and National Identity. Functionalists thinkers such as Emile Durkheim and Talcott Parsons saw national education systems with their top-down national curriculums and examinations as being essential in advanced societies.

It follows that Modernisation Theorists in the 1950s also saw the establishment of education systems as one way in which traditional values could be broken down. If children in developing countries are in school then they can be taught to read and write (which their parents couldn’t have done in the 1950s given the near 100% illiteracy rate at the time), and the brightest can be filtered out through examinations to play a role in developing the country as leaders of government and industry.

According to modernisation theory, school curriculums should be designed with the help of western experts and curriculums and timetables modelled on those of Western education systems – with academic subjects such as English, Maths and History forming core subjects in the curriculums of many developing countries.

However, there are a number of criticisms of the Modernisation Approach to education.

Dependency theorists have pointed out that most people in developing countries do not benefit from western style education. According to DT, education was used in many colonies as a tool of control by occupying countries such as Britain, France and Belgium. The way this worked was to select one quiescent minority ethnic group and provide their children with sufficient education to govern the country on behalf of the colonial power. This divisive legacy continued after colonies gained their independence, with school systems in developing countries proving an extremely sub-standard of education to the majority while a tiny elite at the top could afford to send their children to be educated in private schools, going on to attend universities in the USA and Europe, and then returning to run the country as heads of government and industry to maintain a system which only really benefits the elite, while the majority remain in poverty.

One potential solution to the exclusion faced by the majority of children from education in the developing world comes in the form of Non Governmental Organisations such as Action Aid, who are best known for their Sponsor a Child Campaign, in which any individual in the west can pay £20/ month (or thereabouts) which can fund a child through education. One example of a homegrown version of this charity is the Parikrma Humanity Foundation which essentially ignores the daunting numbers of uneducated children and just focuses on educating one child at a time from the slums of India, to a relatively high level, so that they can escape their poverty for good.

People Centred Development theorists criticise Modernisation Theory because of the fact that Western style curriculums are not appropriate to many people in developing countries. In short, the situations many people in poor countries find themselves in mean they would benefit more from a non-academic education, and more over one that is not explicitly designed to smash apart their traditional societies. According to PCD if people from the west want to help with education in developing countries, they should find out what people in developing countries want and then work with them to meet their educational needs. One excellent example of this is the Barefoot education movement which teaches women and men, many of whom are illiterate, in North West India to become solar engineers and doctors in their own villages, drawing as far as possible on their traditional knowledge. There is one condition people must meet in order to become teachers in this school – they must not have a degree.

It might also be the case that modern technology today means that Western Education systems are simply not required in developing countries. Bill Gates (Head of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the largest Philanthropic charitable organisation in the world which controls over $30 billion of assets, and has a similar amount pledged by wealthy individuals) – who (again unsurprisingly) believes that developing online education courses will change the face of global education in the next 15 years because they can be accessed by anyone with a smartphone. One of the leaders in the development of online courses is the Khan Academy- whose strapline is ‘You can learn anything… for free.

An interesting experiment which suggests this might just work is Sugata Mitra’s ‘hole in wall experiment’ in which he simply put computers in a hole in a wall in various slums and villages around India and just left them there – children picked up how to surf the internet in a matter of days, and even learned some rudimentary English along the way. Mitra’s theory is that children can teach themselves when they work in groups, and his intention is to develop cloud based educational material which will enable children to teach themselves a whole range of subjects.

One problem with leaving education to People Centred Development Approaches or leaving it to children to educate themselves on the internet is that this will probably leave children in poorer developing countries lagging behind in terms of the skills and qualifications required to compete for the best paying jobs in the international job market. In comparison to developing countries, developed countries spend a fortune on their education systems and children spend considerably longer in education, and there is an undeniable link between the successful education systems in South East Asia and the hours invested in education by South East Asian children in countries such as China, South Korea and Singapore and the rapid growth of these economies over the past decades. The problem with this approach is that its success may well be related to the culture of the region which emphasises the importance of individual effort in order to achieve through education.

Relevance to A-level Sociology

SignPostin

Cheers! Glad you like it!

this is very insightful. thank you for an amazing read 🙂