Social Facts are one of Emile Durkheim’s most significant contributions to sociology. Social facts are things such as institutions, norms and values which exist external to the individual and constrain the individual.

The University of Colorado lists as examples of social facts: institutions, statuses, roles, laws, beliefs, population distribution, urbanization, etc. Social facts include social institutions, social activities and [the strata of society – for example the class structure, subcultures etc.]

The video below provides a useful introduction to the concept of social facts….

The video suggests that the concept ‘social fact’ is a broad term designed to encompass the social environment which constrains individual behaviour.

It uses the analogy of a how the physical structure of a room limits our actions (we can only go in and through the door or windows for example; in the same way the social facts which make up our social environment constrains us – norms, values, beliefs, ideologies and so on effectively limit our choices.

Sociology is about identifying the relationship between the social conditions and people’s behaviour.

This second video is a bit more complex…

According to Durkheim, social facts emerge out of collectives of individuals, they cannot be reduced to the level of individuals – and this social reality is real, and it exists above the level of the individual, sociology is the study of this ‘level above the individual’.

As far as Durkheim was concerned this was no different to the concept that human life is greater than the sum of the individual cells which make it up – society has a reality above that of the individuals who constitute it.

A key idea of Durkheim – that we should never reduce the study of society to the level of the individual, we should remain at the level of social facts and aim to explain social action in relation to social facts.

(Not in the video) – this is precisely what Durkheim did in his study of suicide by trying to explain variations in the suicide rate (which is above the level of the individual) through other social facts, such as the divorce rate, the pace of economic growth, the type of religion (all of which he further reduced to two basic variables – social integration and social regulation.

In this way sociology should aim to be scientific, it should not study individuals, but scientific trends at the level above the individual. This is basically the Positivist approach to studying society, as laid down in Durkhiem’s 1895 work ‘The Rules of Sociological Method’.

NB Durkheim’s study of suicide is just about the best illustration of the application of social facts that there is – In which he researched official statistics on suicide in several European countries and found that the suicide rate was influenced by social facts such as the divorce rate, the religion of a country, and the pace of economic and social changed – Durkheim further theorized that the suicide rate increased when there was either too much or too little integration and regulation in society.

The major criticism of Durkheim’s concept of social facts is that the statistics he claims to be ‘social facts’ aren’t – suicide stats are open to manipulation by the people who record them (coroners) – and there is huge potential for several suicides (intentional deaths) to be mis-recorded as open verdicts or accidental deaths and thus we can never be 100% certain of the validity of this data, thus theorising on the basis of cross national comparisons based on said data is risky.

It is possible to apply this ‘social construction critique’ to a range of statistics – such as crime stats, unemployment stats, immigration stats, happiness stats, and a whole load more, which means that while there may be a really existing social world external to the individual, it’s not necessarily possible to know or measure that world with any degree of certainty or to understand how all of the various social facts out there interact with each other. NB This may well explain why no one seems to be able to make predictions about economic crashes, Arab Springs, or election results these days!

Other critics, such as phenomenologists (kind of like precursors to Postmodernists), argue that the whole concept of an external reality is itself flawed, and that instead of one external reality which constrains individuals there are a multitude of more fluid and diverse social realities which arise and fade with social interaction. From this perspective, we may think there is a system of social norms and values out there in the world, but this is only ‘real’ for us if we think it to be real; this is nothing more than a thought, and thus in ‘reality’ we are really free as individuals. (Monstrously free, if you like, to coin a phrase.)

Do Social Facts Exist?

Durkheim’s view of society and the Positivist method have been conceived over 100 years ago, and it has been severely criticised by Interpretivists and Postmodernists, but this hasn’t stopped many researchers from adopting a quantitative, scientific approach to analysing social trends and social problems at the level of society rather than at the level of the individual, and there does seem to be something in the view that society constrains us in subtle and often unnoticed ways, many of which you would’ve come across over the two year A level sociology course.

The suicide rate still varies according to various social factors (‘social facts’?)

For example, after noting that the male suicide rate is 3 times higher than the female suicide rate, and highest for men in their late 40s, This 2016 suicide report by the Samaritans (UK focus) notes that ‘Research suggests that social and economic factors influence the risk of suicide in women as well as men’

Hence as Durkheim said in the 19th century, the decision to kill yourself isn’t just a personal decision, it’s influenced by whether your’re male or female and your age. (As a 43 year old male, I don’t find this graph particularly encouraging, then again at least I’m into ‘the hump’ rather than staring at it from my 30s and with only 8 years of shit to go.)

The birth rate/ total fertility rate seem to be effected by a number of ‘social facts’

Think back to the module on the family – while the decision to have babies seems personal and private, the number of children women have, and the age at which they have them seems to be influenced heavily by society. The decline in the birth rate is now a global trend – and while there are different ’causes’ which have led to its reduction, some of the more common ones appear to be women’s empowerment and education , economic growth and state-promoted family planning.

This isn’t just me saying this, it’s backed up by a whole load of number crunching of global data on birth rates which are summarised in this excellent Guardian article.

According to the The UN Population Fund (UNFPA) there are a number of factors that can play a role in a country’s fertility rates, including its investment in education, the availability of family planning services, the status of women’s rights and the prevalence of early and forced marriage.

“Population dynamics are not destiny,” the UNFPA’s population matters report says. “Change is possible through a set of policies which respect human rights and freedoms and contribute to a reduction in fertility, notably access to sexual and reproductive healthcare, education beyond the primary level, and the empowerment of women.”

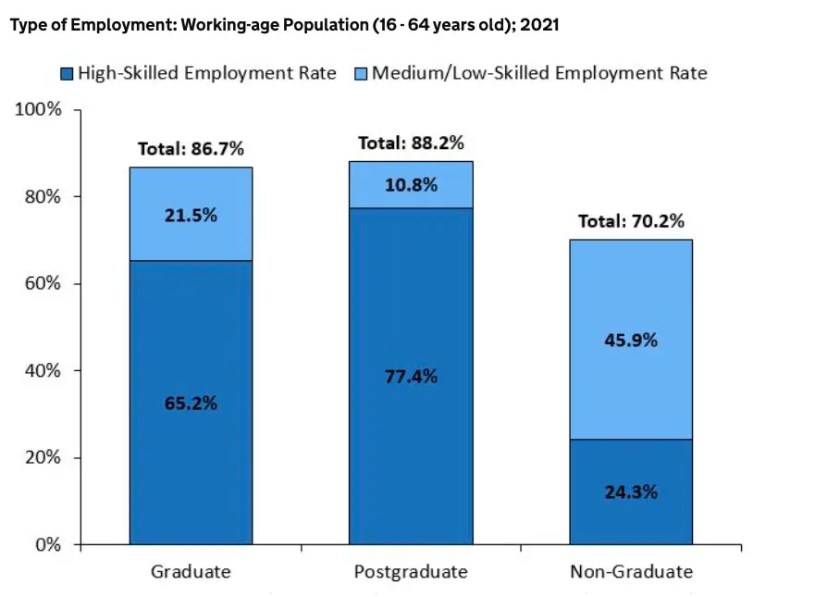

Educational achievement still varies enormously by (the social fact of) social class background

It’s depressing to have to remind you about it, but from the Education module you learnt that social class background has a profound impact on educational achievement. The graph below shows achievement by FSM pupils compared to all other pupils. ‘FSM’ stands for ‘Free School Meals’ – to qualify for FSM status a child needs to be in approximately the bottom sixth of households by income -NB FSM is only a proxy for social class, one indicator of it, the only one we have to hand which is convenient. (The government doesn’t collect information on social class and educational achievement for ideological reasons).

Again if you think back to the lessons on material and cultural deprivation, coming from a poor background seems to weigh heavily on ‘poor kids’ while coming from a middle class background confers material and cultural advantage on the children of wealthier parents. Sad to say but educational results in England and Wales are most definitely NOT a reflection of just intelligence.

For the full report click here

The Spirit Level – Equality as a ‘Social Fact’?

One of the best examples of a Positivist approach to social research carried out in recent years is ‘The Spirit Level’ by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett.– a study of the effects of wealth and income inequality on a whole range of social problems

Chapter by chapter, graph by graph, the authors demonstrate that the more unequal a rich country is,the worse its performance is likely to be in a whole range of variables including:

- life expectancy

- infant mortality

- obesity

- child wellbeing

- amount of mental illness

- use of illegal drugs

- teenage pregnancy rates

- homicide and imprisonment rates

- levels of mutual trust between citizens

- maths and literacy attainment

- social mobility (children rising in social scale compared with their parents)

- spending on foreign aid

The authors consider and eliminate other possibilities, and conclude:

‘It is very difficult to see how the enormous variations which exist from one society to another in the level of problems associated with low social status can be explained without accepting that inequality is the common denominator, and a hugely damaging force.”

Inequalities erode “social capital”, that is, the cohesion of a society, the degree to which individual citizens are involved in their society, the strength of the social networks within it, and the degree of trust and empathy between citizens.

The mechanisms by which inequality impacts on societies, it is suggested, is that individuals internalise inequality, that their psyches are profoundly affected by it, and that that in turn affects physical as well as mental health, and leads to attitudes and behaviours which appear as a variety of social and health problems.’

So if you’ve got an anxiety disorder, blame Thatcher, she’s the one whose government kick started the march towards inequality.

Social Facts… In summary

According to Durkheim (a French dude from the 19th century), society exists at a level above the individual and it kind of has a life of its own. It consists of social facts such as institutions and the class structure which constrain individuals depending on their relation to said social facts.

Durkheim believed that we should limit ourselves to studying ‘social facts’ at the level of society – aim to understand how and why social trends vary, and do this in a scientific way.

Understanding more about how these social forces drive social change, and deriving the laws which govern human interaction is the point of sociology according to Durkheim, and doing this requires us to study social facts at the level of society, there is no need to focus on individuals.

Some of the findings of this type of research based on social facts include…….

- Being male, 40-50, poor, and divorced means you are more miserable and more likely to kill yourself (Oh yeah, I’m not poor, or divorced, so yay I’m OK!)

- Economic growth, female empowerment, and family planning policies have led to women having fewer babies

- Being from a poor household means you’re much more likely to get crap CGSEs

- The more unequal a country in terms of wealth and income the worse of everyone is in pretty much every way imaginable, especially those at the bottom.

So that’s all pretty useful, right? Basically we need to make the world more equal, empower more women, and help poor children and middle aged men more and everything’ll be a whole lot better….