Last Updated on January 25, 2019 by Karl Thompson

The Department for Education publishes an annual report on exclusions, the latest edition published in August 2018 being ‘Permanent and fixed-period exclusions in England: 2016 to 2017.

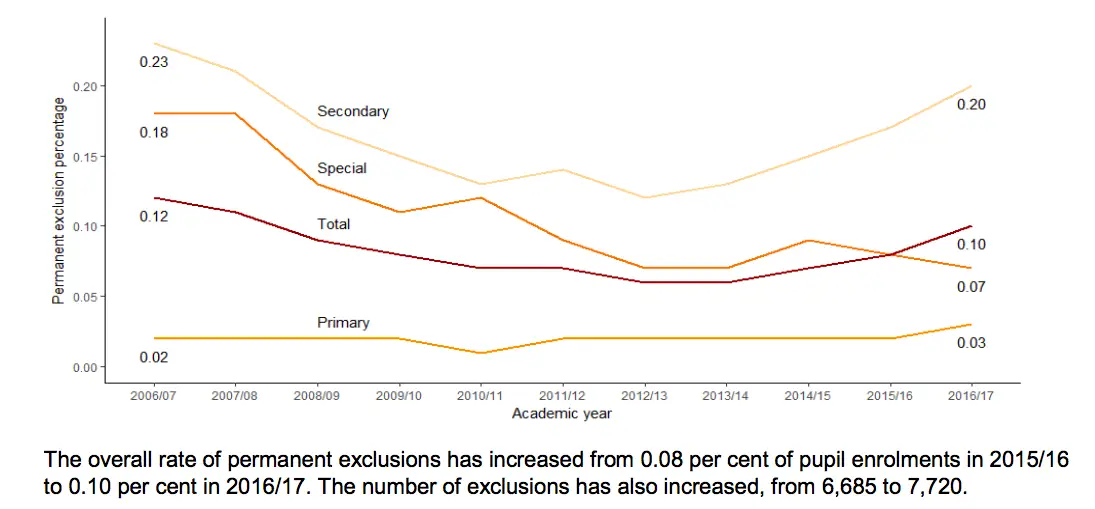

The 2018 report shows that the overall rate of permanent exclusions was 0.1 per cent of pupil enrolments in 2016/17. The number of exclusions was 7,720.

The report also goes into more detail, for example….

- The vast majority of exclusions were from secondary schools >85% of exclusions.

- The three main reasons for permanent exclusions (not counting ‘other’) were

- Persistent disruptive behaviour

- Physical assault against a pupil

- Physical assault against an adult.

Certain groups of students are far more likely to be permanently excluded:

- Free School Meals (FSM) pupils had a permanent exclusion rate four times higher than non-FSM pupils

- FSM pupils accounted for 40.0% of all permanent exclusions

- The permanent exclusion rate for boys was over three times higher than that for girls

- Over half of all permanent exclusions occur in national curriculum year 9 or above. A quarter of all permanent exclusions were for pupils aged 14

- Black Caribbean pupils had a permanent exclusion rate nearly three times higher than the school population as a whole.

- Pupils with identified special educational needs (SEN) accounted for around half of all permanent exclusions

The ‘reasons why’ and ‘types of pupil’ data probably hold no surprises, but NB there are quite a few limitations with the above data, and so these stats should be treated with caution!

Limitations of data on permanent exclusions

Validity problems…

According to this Guardian article, the figures do not take into account ‘informal exclusions’ or ‘off-rolling’ – where schools convince parents to withdraw their children without making a formal exclusion order – technically it’s then down to the parents to enrol their child at another institution or home-educate them, but in many cases this doesn’t happen.

According to research conducted by FFT Education Datalab up to 7, 700 students go missing from the school role between year 7 and year 11 when they are supposed to sit their GCSEs…. Equivalent to a 1.4% drop out rate across from first enrolment at secondary school to GCSEs.

Datalabs took their figures from the annual school census and the DfE’s national pupil database. The cohort’s numbers were traced from year seven, the first year of secondary school, up until taking their GCSEs in 2017.

The entire cohort enrolled in year 7 in state schools in England in 2013 was 550,000 children

However, by time of sitting GCSEs:

- 8,700 pupils were in alternative provision or pupil referral units,

- nearly 2,500 had moved to special schools

- 22,000 had left the state sector (an increase from 20,000 in 2014) Of the 22,000,

- 3,000 had moved to mainstream private schools

- Just under 4,000 were enrolled or sat their GCSEs at a variety of other education institutions.

- 60% of the remaining 15,000 children were likely to have moved away from England, in some case to other parts of the UK such as Wales (used emigration data by age and internal migration data to estimate that around)

- Leaves between 6,000 to 7,700 former pupils unaccounted for, who appear not to have sat any GCSE or equivalent qualifications or been counted in school data.

Working out the percentages this means that by GCSEs, the following percentages of the original year 7 cohort had been ‘moved on’ to other schools.

- 6% or 32, 000 students in all, 10, 00 of which were moved to ‘state funded alternative provision, e.g. Pupil Referral Units.

- 4%, or 22K left the mainstream state sector altogether (presumably due to exclusion or ‘coerced withdrawal’ (i.e. off rolling), of which

- 4%, or 7, 700 cannot be found in any educational records!

This Guardian article provides a decent summary of the research.

Further limitations of data on school exclusions

- There is very little detail on why pupils were excluded, other than the ‘main reason’ formally recorded by the head teacher in all school. There is no information at all about the specific act or the broader context. Labelling theorists might have something to say about this!

- There is a significant time gap between recording and publication of the data. This data was published in summer 2018 and covers exclusions in the academic year 2016-2017. Given that you might be looking at this in 2019 (data is published annually) and that there is probably a ‘long history’ behind many exclusions (i.e. pupils probably get more than one second chance), this data refers to events that happened 2 or more years ago.

Relevance of this to A-level sociology

This is of obvious relevance to the education module… it might be something of a wake up call that 4% of students leave mainstream secondary education before making it to GCSEs, and than 1.4% seem to end up out of education and not sitting GCSEs!

It’s also a good example of why independent longitudinal studies provide a more valid figure of exclusions (and ‘informal’ exclusions) than the official government statistics on this.

I’ll be producing more posts on why students get excluded, and on what happens to them when they do and the consequences for society in coming weeks.

This is a topic that interests me, shame it’s not a direct part of the A level sociology education spec!

Leave a Reply