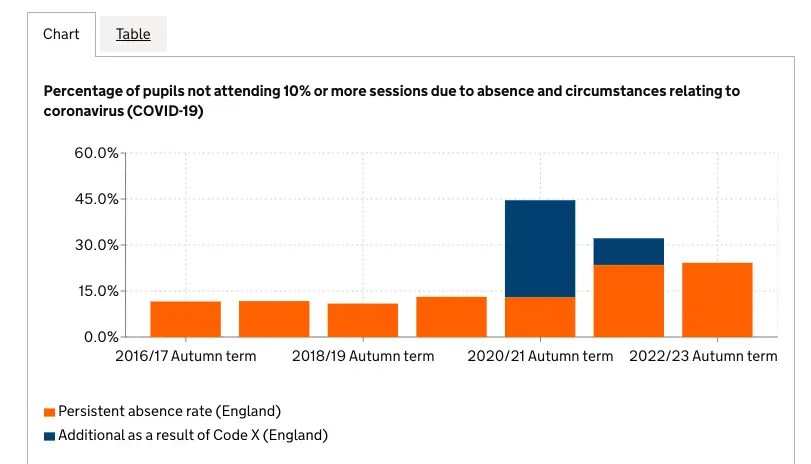

The Education Secretary, Gillian Keegan recently claimed that school funding was at a record high. She claimed that schools were being funded at the level of £60 billion a year, the highest per-pupil figure in history.

However this is not accurate, according to a recent episode of More or Less on Radio 4.

According to Luke Sibieta, research fellow at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS):

Between 2010 and 2019 spending per pupil fell by about 9% in real terms. Since 2019, the government has increased school funding. Spending per pupil should be back to about where it was in 2010 by 2025, but only just.

Prior to 2010 (when the Tories came to power) real-terms spending on education per pupil increased year on year. It was true to say that school spending was at ‘record levels’ nearly every year all the way back to 1945.

The fact that this is now worth mentioning highlights the historically unusual cuts to school funding under Tory government for the last decade.

The above figures from the IFS refer to spending on all pupils from the age of 3 all the way up to age 19.

How the government manipulated the official statistics

The government uses spending on pupils aged only 5-16. By selecting these figures the government is able to paint a more positive picture of school funding over the years. Spending on 5-16 year olds shows flat spending during 2010-2015, then a cut to 2019. Then after this an increase.

The government figures disguise the severe 25% cuts they have made to sixth forms over the last decade.

The government figures also disguise cuts to Local Education Authorities which used to fund many important services to schools. Such services included SEN spending and running administrative services such as pay-rolls for example. Local Authority education funding for these services have been cut by 50% between 2010 and 2019. Schools now have to pay for these things themselves out of smaller budgets.

The government figures also disguise severe cuts to capital spending. Spending on school buildings and repairs was 20% lower in the last three years than it was in the late 200os.

Relevance to A-level sociology

This is most relevant to the module in research methods.

This brief update is a good example of government bias in the use of statistics. The government deliberately selects a narrow age-range to get a positive spin or bias on the education spending figures.

However their claims are kept in check by the more objective IFS. Their more complete data with a broader age range (3-19) shows us that spending hasn’t been as much as the Tory’s claim.

Overall this is a lesson in why you can’t trust official government statistics!

Find out More

You might like this report on annual schools spending by the IFS.