This post explores the long and short term trends in marriage, divorce and cohabitation in the United Kingdom.

Marriage, Divorce and Cohabitation: Key Facts

- There are approximately 230 000 marriages a year in England and Wales. This is down from just over 400 000 a year in the late 1980s.

- The marriage rate halved between 1991 and 2019. For women the rate declined from 34/1000 in 2019 to just 18/ 1000 in 2019.

- The average age for marriage is 34 for men and 32 for women. The average age of marriage is getting older. In 1967 the average ages were 27 for men and 25 for women.

- The number of church weddings is declining. Only 18.2% of weddings were church ceremonies in 2019.

- The number of cohabiting couples is increasing. In 2022 18.4% of families were cohabiting. This is up from 15.7% of families in 2012.

- There has been a long term increase in the divorce rate since the 1950s. However the divorce rate declined between the early 2000s and 2018. More recently it has been increasing again.

- In 2022 there were 9 divorces per 1000 marriages. There were a total of 113 500 divorces in 2021.

Where possible I have included data from the latest Office for National Statistics (ONS) publications on marriage, cohabitation and divorce from 2023. However sometimes I have used previous publications because those show longer term trends or analyse the data in different ways.

Marriage Statistics

There was a long term decrease in the number of marriages per year since the late 1960s when there were just over 400 000 marriages every year, until around 2008, when the number hit around 230 000.

There has been a slight increase since then and there are now around 240 000 marriages every year in the UK, and this number has been relatively stable since 2008.

Marriage Rates in England and Wales

The marriage rate is the number of people who get married per thousand unmarried people. The marriage rate is slightly higher for men than for women, although the difference has decreased over the last 30 years (1).

The marriage rates in England and Wales almost halved between 1991 and 2019 for both men and women.

In 1991 the marriage rate for men was 39/1000, this had declined to 20/1000 by 2019.

For women the figures were 34/1000 and 18/1000 respectively.

During the lockdown of 2020 the marriage rate plummeted to only 6/1000 for both men and women.

I would expect the marriage rate to be similarly low in 2021, but then to increase in 2022 and maybe even 2023 with people having delayed getting married increasing the numbers. I think we will have to wait until 2024 for marriage rates to get back to normal and be able to compare the long term trend.

What is the average age of Marriage?

In 2019 the average age of marriage for men was 34.3 years for men and 32.3 years for women (2).

Looking at the longer term trend the average age of marriage has increased by almost ten years since the the 1960s.

In 1967 the average age of marriage was 27 for men and 25 for women.

The 2019 ONS data also shows us recent trends in the ages of same sex married couples getting married. Same-sex couples get married slightly older compared to opposite sex couples.

The Decline of Church Weddings

The above chart shows the drastic decrease in religious marriages, down to only 18.2% of all marriages by 2019. 82.8% of marriages in 2019 were civil ceremonies.

90% of couples cohabited before marrying in 2017, up from 70% in the late 1990s.

Limitations with Marriage Statistics

The ONS only publishes annual marriage statistics three years after the year marriages took place. This is because there can be a delay of up to 26 months from clergy and other official bodies in recording the marriages. The ONS estimates that one year on from marriages taking place, around 4% of them have still not been recorded. The three year delay is to make sure data recording is accurate.

Cohabitation Statistics

The proportion of cohabiting households in England and Wales has increased in the last decade.

18.4% of families were cohabiting in 2022. This is an increase from 15.7% of families in 2012.

Younger couples are much more likely to cohabit

According to UK Census, in 2021 (5)

- 89% of couples aged 20-24 were cohabiting.

- 45% of couples aged 30-34 were cohabiting.

- 24% of couples aged 40-44 were cohabiting.

- This declines to less than 10% for all couples aged 65 and over.

All aged groups were more likely to cohabit in 2021 compared to 2011, except for the very oldest age category of 85s and over.

Divorce Statistics

Since the 1960s there has been a long term increase in the divorce rate.

The number of Divorces per year increased rapidly following the Divorce Reform Act of 1969, and then increased steadily until the early 1980s. In the late 1950s, there were only around 20 000 Divorces per year, by the early 1980s this figure had risen to 160 000 per year (quite an increase!)

It then stabilised for about 10 years and then started to decline in 2003, the number of divorces per year is still in decline. There are currently just under 90 000 divorces per year in England and Wales.

The Divorce Rate

The Divorce Rate was extremely low in the late 1950s, at only 2.5 per 100 000 married couples (3)

The Divorce Reform Act of 1969 led to this increasing rapidly to 10 per thousand in just a few years, by the early 1970s.

The Divorce Rate continued to increase until the early 1990s, when it hit almost 15 per thousand married couples. Since then it has been falling and currently stands at 7.5

The divorce rate has fallen since 2004

The divorce rate has fallen overall since 2004, but increased in recent years.

From 2004 to 2018 the UK divorce rate fell from 13 per 1000 marriages to just above 7 per 1000 marriages, the low point since before the 1969 Divorce Act.

The divorce rate has increased slightly since 2018, but only slightly and is currently at 9 divorces per 1000 in 2022.

The total number of divorces in 2021 was 113, 505.

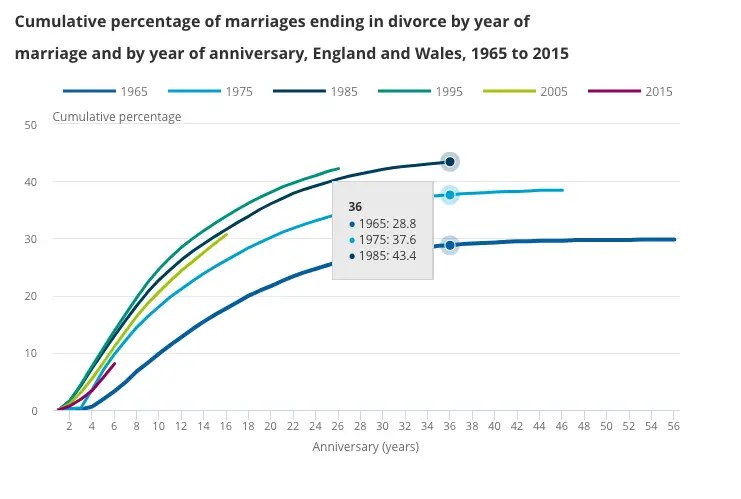

What percent of marriages end in divorce?

The percentage of marriages which end in divorce depends on the year in which the marriage took place.

- For those married in 1965, 28.7% of marriages had ended in divorce after 35 years.

- For those married in 1975, 37.6% of marriages had ended in divorce after 35 years.

- For those married in 1985 43.4% of marriages had ended in divorce after 35 years.

- For those married in 1995 41.7% of marriages had ended in divorce after 25 years, and the divorce rate looks set to be higher by 35 years.

- Those married in 2005 and 2015 have lower divorce rates for younger marriages, so are set to have divorce rates after 35 years somewhere between 36% and 42%.

For those who got married in 2005, 20.7% had got divorced after 10 years and 29.2% after 15 years.

How long does the average marriage last?

The length of marriage is increasing. For marriages which end in divorce, the median length of a marriage was 12.3 years.

For same sex couples the median length of marriage is much shorter. It is 5.9 years for male couples and 5.3 years for female couples.

Opposite and Same-Sex Divorces

There were 111. 934 opposite-sex resources in 2021, 63% of which were petitioned by females and 37% petitioned by men.

There were 1571 same-sex divorces, of which 67% were petitioned by female couples. The number of same-sex divorces has increased every year since they first became possible in 2015, following the introduction of same-sex marriage shortly before.

Limitations with divorce statistics

Divorce statistics only show marriage break ups which are final. They don’t show married couples who are separated.

There are no formal official break up statistics for cohabiting couples. Hence it’s difficult to compare break up rates for married and cohabiting couples.

It is difficult to compare the rates of divorce between same-sex and opposite-sex couples. Same sex marriage has only been around for less than a decade, and most divorces happen after several years of marriage. We will have to wait a few more years at least to be able to make valid comparisons.

Careful with comparisons! The Divorce Rate shows a slightly different trend to the ‘number of divorces’. The former is relative to the number of married couples!

Main sources used to write this post

(1) Office for National Statistics (May 2023): Marriages in England and Wales 2020.

(2) ONS: Marriages in England and Wales 2019.

(3) ONS: Divorces in England and wales 2021.

(4) ONS: Families and Households in the UK 2022.

(5) People’s living arrangements in England and Wales: Census 2021.

Other Sources

Office for National Statistics: Divorces in England and Wales 2018.

ONS: Marriages in England and Wales 2017.

ONS: Marriage and Divorce on the Rise, Over 65 and Over.

Signposting

This post is relevant to the ‘marriage and divorce’ topic which is usually taught as the second topic within the AQA’s families and households A-level sociology specification.