The UK government’s main policy to help students catch up on missed schooling during the Pandemic has been to provide extra funding to schools on a per pupil basis.

The extra funding amounts to around £600 million, which sounds like a lot, but this is only equivalent to £80 per pupil, but with more being allocated for students with special educational needs.

If you are studying for this years A-level sociology exams you should consider and critically evaluate this policy, not only as it should have affected your own life, but also because you should be able to use this in the PAPER 1 exam as ‘education policies’ is the topic selected in the pre-release advanced information – something about Policies WILL come up, most likely an essay, and so you SHOULD be able to use material on covid catch-up policies.

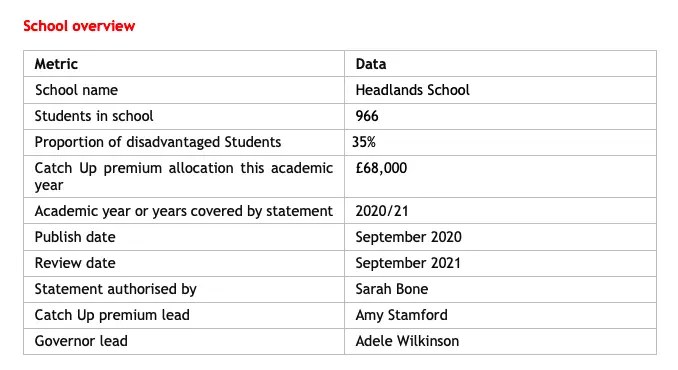

To give you an idea of just how little money this is once it gets to schools check out this policy response document from one school.

So that’s £68 000 for 966 pupils.

Let’s assume that this school is going to focus on the 35% disadvantaged pupils….

So that would be £68 000 for 350 pupils (approximately), each of whom would have missed around 20 weeks of schooling over the last two years.

So what can that $68K buy for the school….

Let’s assume like for like and that they’re going to fund 6 months worth of catch up, then that £68K would buy….

- About 3 qualified teachers (pay their salaries for 6 months) – with classes of 35 and 5 lessons of an hour a day (to make the maths easier) that could mean an extra 2.5 hours of lesson per pupil per week.

- With smaller classes of 15-20 that’s 1 hour and 15 minutes a week.

- Or about 3400 hours of one on one tuition (at £20 an hour) – a total 10 hours each per pupil over 6 months.

- Or they could pay for around 6 Full time support workers, but the benefits of those are more difficult to quantify.

NB all of the above assumes ONLY the 35% of disadvantaged students getting extra help at the same rate, it doesn’t factor in SEN pupils and assumes 65% of students get nothing.

So TLDR – this catch up funding means 10 hours of extra tuition for disadvantaged pupils for 6 months in smallish classes of around 15 pupils.

So ask yourself – is 10 hours enough to catch up on 20 weeks of missed schooling?

Is it fair that 65% of pupils get nothing? (In my hypothetical model)

Oh and one final thing, if you feel as if you’ve got no extra support to catch up following lessons lost due to Covid, this might explain why!

Relevance to A-level Sociology

This is directly relevant to the Education topic, and should be useful in this year’s 2022 exam!