Almost 38% of U.K. students were awarded first-class honours degrees in 2021, compared to only 15.7% in 2011.

Some of this increase is due to universities awarding more generous degrees during the Covid-19 Pandemic, which mirrors what happened with the over-grading at GCSE and A-level:

However, we can also see from the above chart that this grade inflation has been increasingly steadily nearly every year since 2010-11.

According to REFORM (2) there is also a longer term trend in degree level grade-inflation: In the mid 1990s only 7% of degrees were awarded a first-class honours.

Why are more students being awarded first-class degrees?

It is highly unlikely that the type of students who enter university today are twice as capable of achieving a first-class degree than those students who entered university a decade ago.

Or put another way there aren’t twice as many super-intelligent or super-degree-exam trained students today compared to back in 2013.

Some recent statistical analysis (1) by the Office for Students backs this up: they found that over half of the increase in degree-grades cannot be accounted for by factors such as changes in provider, geographical area, subject, entry qualifications, age, disability, ethnicity, or sex.

Why is there grade-inflation?

Three possible reasons include:

- Universities are grading more leniently.

- Universities are trying to close the achievement gap

- The pressures of marketisation?

Universities grade more leniently today

Analysis by REFORM (2) suggests that universities are getting more lenient in awarding grades. In other words, they are awarding higher grades for lower standards of work.

This is (according to REFORM) happening in two ways:

Universities have changed the algorithms they use to translate raw marks into degree grades, one specific change mentioned is that they are now more lenient towards borderline students: if you’ve got 68% overall you’re now more likely to be tipped over into a first-class honours degree than you would have been ten years ago.

University staff have also come under pressure to mark more leniently, with several staff publicly complaining over the years about the lowering of standards.

Closing the achievement gap

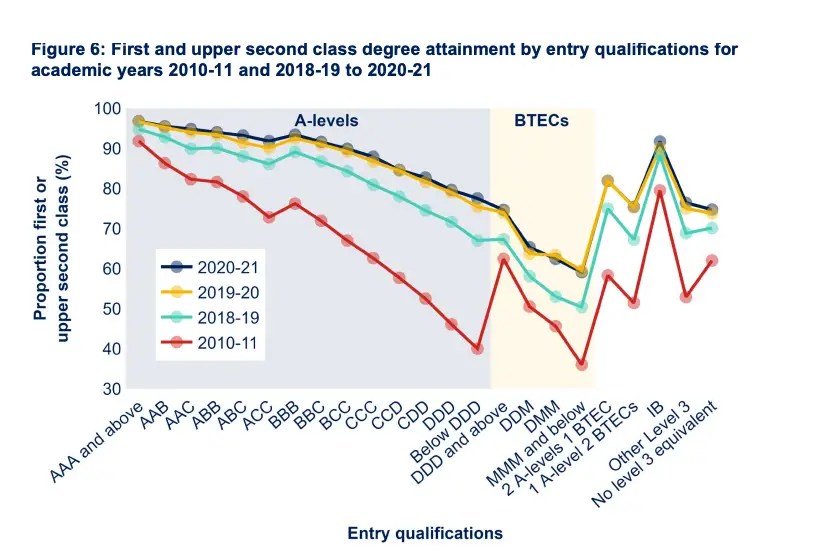

Maybe one upside of grade inflation is that we find that students with worse A-levels are gradually achieving BETTER grades of degrees over time. For example, in 2011 only 40% of students who achieved three Ds at A-level achieved a first or 2.1 degree, by 2021 this figure was 80%.

This is in part how universities justify grade inflation: that it helps them close their disadvantage gap, as it tends to be students from lower income backgrounds who enter with worse A-levels, and we can see from the above chart that the achievement gap has narrowed over time.

The pressures of marketisation?

Students now pay £9000 a year in tuition fees, they didn’t in the mid 1990s.

This may help explain why 38% of students now get firsts compared to only 7% in the mid 1990s.

This could be because of either or both students working harder because they are paying or universities gradually shifting to give students what they are paying for, which is a decent degree at the end of the day!

The problems with grade inflation

While individual students who get a first class degree may feel best-chuffed, when 38% of them are getting the same, the degree is worth less: so many students now get them it is almost like just a standard degree and there is more competition going into the labour market.

And there are question marks over the validity of today’s degrees. If I was en employer and had two candidates for a job: a 2022 graduate with a first-class degree and a 2012 graduate with a 2.1, I would be thinking those degrees are really the same class, just graded at different standards.

In global terms grade inflation reduces the credibility of UK Higher Education market.

Signposting and related posts

This material is relevant to the education module, although not necessarily of direct relevance to A-level sociology this should be of interest to recent graduates: if you have a first-class degree then your prospective employers may well be suspicious of its validity, so don’t rest on your laurels!

To return to the homepage – revisesociology.com

Sources

(1) Office for Students (2022) Analysis of Degree Classifications Over Time: Changes in Graduate Attainment from 2010-11 to 2020-21.

(2) Reform (2018) A degree of Uncertainty: An Investigation into Grade Inflation in Universities.