Is life in the UK getting better or worse?

This post looks at a few economic and social indicators to see what they suggest about trends in desirable social goods such as economic growth, employment and happiness and less desirable social problems such as crime, mental ill-health and suicide.

The point of this posts is to showcase some of the official statistics we might use to judge the state of the nation. These are the kind of stats we can use to evaluate the Functionalist view that ‘everything in society is generally OK’, compared to other more critical perspectives such as Marxism, Feminism or even Postmodernism.

You should always be critical of the validity of statistics, especially since most of the stats below are official statistics – they are collected by government agencies…

A social or economic indicator might suggest life in the UK is generally getting better or worse, but this might not actually be the case when you scratch beneath the surface.

For example, an increase in recorded crime may not be because of an underlying increase, but rather because people are more aware of certain types of crime and more likely to report those crimes.

Similarly, a decrease in unemployment may just be because more people are fearful of claiming benefits, even though they need them, because of the increased hassle and stigma of claiming them.

Any statistics that use averages may also give us a misleading picture of the ‘health of the nation’. For example, average income can trend upwards, but this doesn’t tell us how that income is distributed – it may mean the top 1/10th getting a lot richer and the bottom 1/10th getting a lot poorer.

Averages can also hide wide variations in how social goods and harms are distributed by gender and ethnicity and age. The male suicide rate is around three times higher than the female suicide rate.

Employment is increasing, unemployment is declining

The employment rate is at a record high of 76.3%, while the unemployment rate has been declining for 6 years, and stands at a very low 3.8%

Source: Labour Market Overview, January 2020.

Suicide Rates have shown a recent increase

In 2018, a total of 6,507 suicides were registered in the UK, equivalent to 11.2 deaths per 100 000 of the population.

Suicide rates have been steadily decreasing for the last 40 years, but there was a statistically significant increase from 2017 to 2018.

It’s also worth noting that the male suicide rate is three times higher than the female suicide rate.

Sources: Suicides in the UK: 2018 Registrations.

Fewer households in absolute poverty, the same amount in relative poverty

If we look at households in ‘absolute low income’ (the bottom two graphs below) then we see a decline. Focusing on the ‘after housing costs’ statistics:

- In 2002/03 24% of households were in absolute low income, compared to only 19% in 2017/18.

- If we look at relative low income, there is no change over time, 22% of households are still classified as low income households.

Source: Households Below Average Income.

Crime rates are remaining stable

However, some types of crime have increased recently

Robbery and knife crime have increased recently, although there are very few cases of these types of crime compared to theft and fraud, and while the later has increased, the impact of fraud on victims is probably less harmful than for most other types of crime.

Source: Crime in England and Wales

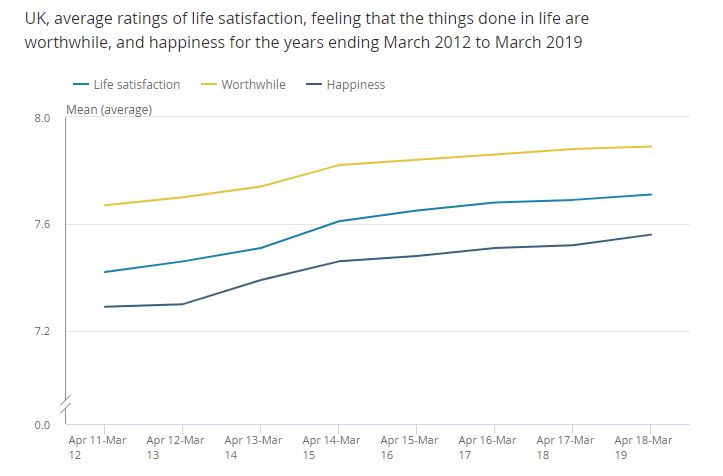

People are happier

The mean happiness score (/10) for the UK population has increased to all time high of 7.56. ‘Life satisfaction’ and ‘worthwhileness’ scores are also increasing

Anxiety levels are stable

The mean anxiety score (/10) has remained stable at just below 3/10 for half a decade, while the percentage of people reporting high levels of anxiety remains at just under 20%.

Source for the above two sets of stats: Personal and Economic well-being indicators.

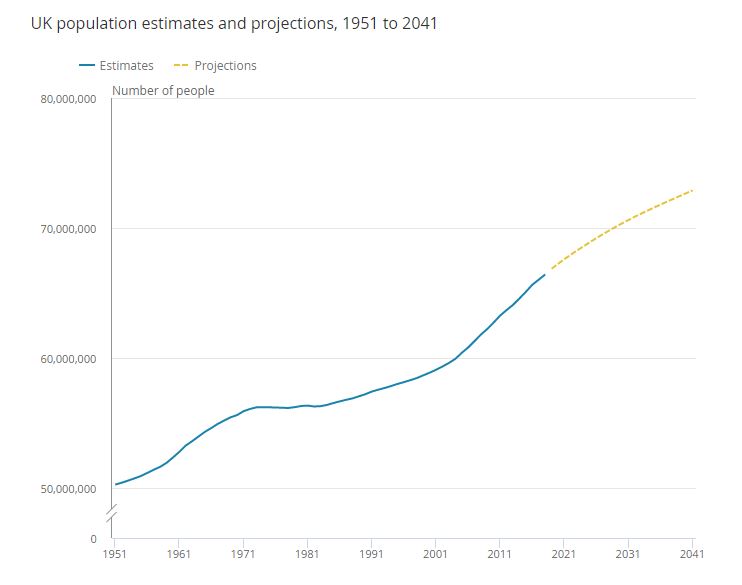

The UK’s Population is Increasing

In 2018, the UK’s population reached 66.4 million people, with a growth rate of 0.6% and immigration being the main reason for population growth.

The population is increasing at roughly 350 000 people per year, just over 100 000 of these are due to ‘natural change’ (more births than deaths) while just over 200 000 are due to net migration (more people immigrating than emigrating.

Source: Overview of the UK population.

Conclusion: Is life in the UK getting better or worse?

On balance I’d say that the official statistics above suggest that, on average, life in the UK is getting better:

- Employment and poverty are both down.

- Crime is generally down

- Happiness is increasing and anxiety is stable

However, there has been a recent spike in the suicide rate and some types of violent crime are up.

It’s very difficult to say whether or not the increasing population is a positive or a negative: clearly the fact that this is driven mainly by immigration concerns a lot of people, but possibly we need migration to offset the increasing dependency ration associated with the aging population, so this might actually be a good sign!

Question: what other stats do you think should be included in the above?