People spend four hours a day on average on their phones, which is equivalent to 60 full days a year, or one quarter of their waking lives.

People are literally addicted to video games, social media, pornography and online shopping – and the numbers who are addicted to technology are growing.

We already find it difficult to switch off from the many apps on our phones and this could be about to get much worse with FaceBook, Google and Microsoft ploughing billions of pounds into constructing the MetaVerse.

These are just some of the claims that some experts make about the addictive nature of technology, but is this addiction to technology actually real?

Elaine Moore, a tech columnist for the Financial Times subjected these claims to critical analysis in a recent Radio 4 analysis podcast: Addiction in the Age of the MetaVerse.

Addiction to video Games

According to Supply Gem (Accessed November 2023) the video games industry is valued at between $221 billion and $385 billion, and there are between 3.09 and 3.26 billion gamers worldwide.

What drives a lot of that revenue are online games such as Fortnite and Call of Duty, games which are immersive, in real time and are played most obsessively by children and young adults.

Teachers have already raised concerns about the amount of time children spend playing these games and when virtual reality headsets are introduced they can become even more immersive and addictive.

The World Health Organisation recently added Gaming Disorder to the classification of Diseases.

Ruth Lockwood from the NHS run centre for gaming disorder defines addiction to gaming as a lack of control over the amount of time an individual spends playing computer games, a tendency to prioritise gaming over other areas of one’s life to the detriment of other life activities. It is a compulsion to play video games even when there are negative consequences to doing so!

According to the experts above, gaming addiction is a real and recognised addiction and it is something that the NHS provides help for.

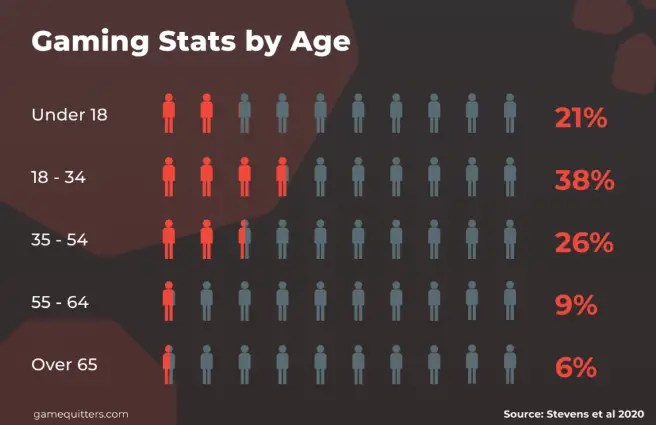

According to meta-analysis conducted in 2021 (and summarised by Game Quitters) 3-4% of gamers are addicted to video games, but the percentages vary considerably by age:

But what about other aspects of tech are they addictions too?

Smart Phones and Addiction

Over 80% of the UK population now own a smart phone, with the figure being nearly 100% for the under 50s. People on average spend four hours a day on their phones which is 60 full days a year or 25% of our waking lives.

A recent 2019 YouGov survey found that 59% of 18-34 year olds would feel anxious if they were without their smartphones for a day because ‘they wouldn’t be able to instantaneously communicate with their friends or family’

Some people are on their phones so much that there is even a term – ‘fubbing’ which means scrolling through your phone while you’re in the middle of a conversation.

If you think you are spending too long on your phone then you might want to try The Smart Phone Compulsion Test developed by David GreenField and the Centre for Internet and Technology Addiction.

Pretty much anyone who takes that test is going to fail, and Catherine Price suggests this doesn’t mean that the test is invalid, rather it means that all of us have problematic relationships with our phones.

Smartphones are addictive by design

If you wanted to invent a device that would make the population perpetually distracted and isolated you would probably end up with the smart phone.

Many design features on Smart Phones are deliberately made to be addictive, evidence for this is that many design features mimic those of slot machines, which are widely regarded as some of the most addictive machines in the gambling industry.

This is especially true of any apps which rely on advertising as advertisers’ revenue increases the more time we spend on these apps, and the more attention we give them!

It’s also worth noting that slot machine addiction was the first officially recognised behavioural addiction in the United States.

Catherine Price has is author of How to Break up with your Phone – a 30 Day Plan to Take Back your Life. She argues that Smart Phones have the power to change the way our brains work.

However her book reminds us that our time and attention are finite and that maybe continually scrolling through our phones isn’t the best use of our time!

We cannot do two cognitively demanding things at once – for example we can’t think of two things at the same time, so in layman’s terms it is impossible for us to multitask.

Problems with Smartphone addiction

Anna Lembke, a Professor of Psychiatry and author of ‘Dopamine Nation‘ points out that SmartPhones light up the ‘reward pathway’ in the brain, from where dopamine is released, in the same way drugs and alcohol does.

There’s no blood test or brain scan to test for this type of addiction, instead researchers use Phenomenology – looking at individual experiences and the way patterns are repeated.

People who are addicted are in an altered state: their gremlins are now driving the bus. The prefrontal cortex which is necessary for factoring in future consequences and deferred gratification goes offline!

People in such a condition, such as compulsive tweeters fail to appreciate how their reward system has been hijacked and see their addictive behaviour as something they need to do.

Advantages of Smart Phones

James Ball, author of ‘The System: Who Owns the Internet, and How it Owns Us‘ is sceptical about the idea that everyone is addicted to their phones.

He argues that tech leads to behaviours that look like they may be addictions but aren’t necessarily addictions.

A phone fulfils different needs all at the same time – we might be having a coffee with a friend and our phones allow to us to check in with other people quickly while still having that coffee.

So possibly we shouldn’t interpret someone checking their phone every five minutes as being a ‘compulsion’ – rather it is something that enables us to effectively manage busy lives – and if it wasn’t for the smartphone allowing us to check-in with other people so easily maybe we wouldn’t be be meeting that friend for an IRL coffee in the first place.

The Metaverse

The MetaVerse is a digital reality that exists in parallel to actual reality.

Some authors think the idea of the Metaverse will be so compelling that we’ll forget to log off from the internet altogether!

Computers have become smaller and the way we interact with them has become more and more intuitive and the Metaverse evolves this make computers invisible, it actually extends into our reality, impinges on it!

Facebook, Google and Apple are all very interested in the Metaverse and are investing huge sums of money into it. Meta alone invested $10 billion in 2021 and all major companies are developing their own head sets.

The merging of the real and virtual world could have sever implications for people’s mental health as it could allow people to block out aspects of their realities that they don’t like and don’t want to deal with, but they would have to allow

The Metaverse could get more and more potent, more addictive – like PacMan isn’t going to do it for a five year old today!

And the government are very unprepared for this next step in the evolution of virtual reality. A recent Digital White Paper didn’t even mention the Metaverse once. The government seems to be on the back foot and unable to anticipate what’s going to happen in the future.

A moral panic over the Metaverse?

James Ball doesn’t think we are into an age of hyper-seductive targeted marketing in the Metaverse given how inaccurate the current targeted advertising is!

There are also possible advantages – motivational apps for developing good behaviours such as walking more or giving up drinking, and we are rewarded with badges for example.

Signposting and Relevance to A-level Sociology

The material above is mainly relevant to the media option at A-level sociology, but this should also be of general interest to anyone with a Smartphone!

To return to the homepage – revisesociology.com