Sociological Perspectives on the family include Functionalism, Donzelot’s conflict perspectives, Liberal and Radical Feminism, the New Right and New Labour.

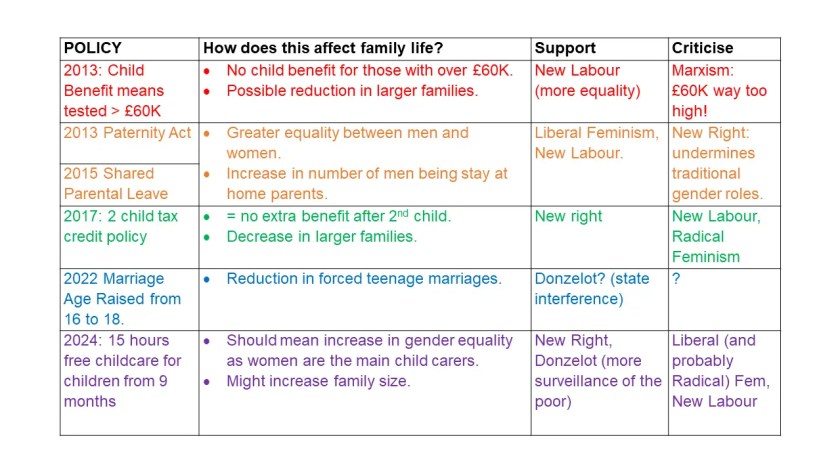

There are several social policies you can apply these perspectives too: everything from the 1969 Divorce Act to the 2022 marriage act.

Perspectives on family policy summary:

The two grids below summarise what family policies different sociological perspectives might support or criticise.

The main blog post below goes into much more depth….

The Functionalist View of Social Policy and The Family

Functionalists see society as built on harmony and consensus (shared values), and free from conflicts. They see the state as acting in the interests of society as a whole and its social policies as being for the good of all. Functionalists see policies as helping families to perform their functions more effectively and making life better for their members.

For example, Ronald Fletcher (1966) argues that the introduction of health, education and housing policies in the years since the industrial revolution has gradually led to the development of a welfare state that supports the family in performing its functions more effectively.

For instance, the existence of the National Health Service means that with the help of doctors, nurses, hospitals and medicines, the family today is better able to take care of its members when they are sick.

Criticisms of the functionalist perspective

The functionalist view has been criticised on two main counts:

- It assumes that all members of the family benefit equally from social policies, whereas Feminists argue that policies often benefit men more than women.

- It assumes that there is a ‘march of progress’ with social policies, gradually making life better, which is a view criticise by Donzelot in the following section.

Adapted from Robb Webb et al

A Conflict Perspective – Donzelot: Policing the Family

Jacques Donzelot (1977) has a conflict view of society and sees policy as a form of state power and control over families.

Donzelot uses Michel Foucault’s (1976) concept of surveillance (observing and monitoring). Foucault sees power not just as something held by the government or the state, but as diffused (spread) throughout society and found within all relationships. In particular, Foucault sees professionals such as doctors and social workers as exercising power over their clients by using their expert knowledge to turn them into ‘cases’ to be dealt with.

Donzelot applies these ideas to the family. He is interested in how professionals carry out surveillance of families. He argues that social workers, health visitors and doctors use their knowledge to control and change families. Donzelot calls this ‘the policing of families’.

Surveillance is not targeted equally at all social classes. Poor families are much more likely to be seen as ‘problem families’ and as the causes of crime and anti-social behaviour. These are the families that professionals target for ‘improvement’.

For example as Rachel Condry (2007) notes, the state may seek to control and regulate family life by imposing compulsory Parenting Orders through the courts. Parents of young offenders, truants or badly behaved children may be forced to attend parenting classes to learn the ‘correct’ way to bring up children.

Donzelot rejects the Functionalists’ march of progress view that social policy and the professionals who carry it out have created a better society. Instead he sees social policy as oppressing certain types of families. By focussing on the micro level of how the ‘caring professions’ act as agents of social control through the surveillance of families, Donzelot shows the importance of professional knowledge as a form of power and control.

Criticism of Conflict perspectives

Marxists and Feminists criticise Donzelot for failing to identify clearly who benefits from such policies of surveillance. Marxists argue that social policies generally operate in the interests of the capitalist class, while Feminists argue men are the beneficiaries.

Adapted from Rob Webb et al

The New Right and Social Policy

The New Right have had considerable influence on government thinking about social policy and its effects on family. They see the traditional nuclear family, with its division of labour between a male provider and a female home maker as self-reliant and capable of caring for its members. In their view, social policies should avoid doing anything that might undermine this natural self-reliant family.

The New Right criticise many existing government policies for undermining the family. In particular, they argue that governments often weaken the family’s self-reliance by providing overly generous welfare benefits. These include providing council housing for unmarried teenage mothers and cash payments to support lone parent families.

Charles Murray (1984) argues that these benefits offer ‘perverse incentives’ – that is, they reward irresponsible or anti-social behaviour. For example –

- If fathers see that the state will maintain their children some of them will abandon their responsibilities to their families

- Providing council housing for unmarried teenage mothers encourages young girls to become pregnant

- The growth of lone parent families encouraged by generous welfare benefits means more boys grow up without a male role model and authority figure. This lack of paternal authority is responsible for a rising crime rate amongst young males.

The New Right supports the following social polices

- Cuts in welfare benefits and tighter restrictions on who is eligible for benefits, to prevent ‘perverse incentives’.

- Policies to support the traditional nuclear family – for example taxes that favour married couples rather than cohabiting couples.

- The Child Support agency – whose role is to make absent dads pay for their children

Criticisms of the New Right

- Feminists argue that their polices are an attempt to justify a return to the traditional nuclear family, which works to subordinate women

- Cutting benefits may simply drive many into poverty, leading to further social problems

Feminism and Social Policy

Liberal Feminists argue that that changes such as the equal pay act and increasingly generous maternity leave and pay are sufficient to bring about gender equality. The following social policies have led to greater gender equality:

- The divorce act of 1969 gave women the right to divorce on an equal footing to men – which lead to a spike in the divorce rate.

- The equal pay act of 1972 was an important step towards women’s independence from men.

- Increasingly generous maternity cover and pay made it easier for women to have children and then return to work.

However, Radical Feminists argue that patriarchy (the ideal of male superiority) is so entrenched in society that mere policy changes alone are insufficient to bring about gender equality. They argue, for example, that despite the equal pay act, sexism still exists in the sphere of work –

- There is little evidence of the ‘new man’ who does their fair share of domestic chores. They argue women have acquired the ‘dual burden’ of paid work and unpaid housework and the family remains patriarchal – men benefit from women’s paid earnings and their domestic labour.

- Some Feminists even argue that overly generous maternity cover compared to paternity cover reinforces the idea that women should be the primary child carer, unintentionally disadvantaging women

- Dunscmobe and Marsden (1995) argue that women suffer from the ‘triple shift’ where they have to do paid work, domestic work and ‘emotion work’ – being expected to take on the emotional burden of caring for children.

- This last point is more difficult to assess as it is much harder to quantify emotion work compared to the amounts of domestic work and paid work carried out by men and women.

- Class differences also play a role – with working class mothers suffering more because they cannot afford childcare.

- Mirlees- Black points out that ¼ women experience domestic violence – and many are reluctant to leave their partner

New Labour and Family Policy

New Labour was in power from between 1997 – 2010. There are three things you need to know about New Labour’s Social Policies towards the family

1. New Labour seemed to be more in favour of family diversity than the New Right. For example –

- In 2004 they introduced The Civil Partner Act which gave same sex couples similar rights to heterosexual married couples

- In 2005 they changed the law on adoption, giving unmarried couples, including gay couples, the right to adopt on the same basis as married couples

2. Despite their claims to want to cut down on welfare dependency, New Labour were less concerned about ‘the perverse incentives of welfare’ than the New Right. During their terms of office, they failed to take ‘tough decisions on welfare’ – putting the well-being of children first by making sure that even the long term unemployed families and single mothers had adequate housing and money.

3. New Labour believes in more state intervention in family life than the New Right. They have a more positive view of state intervention, thinking it is often necessary to improve the lives of families.

For example in June 2007 New Labour established the Department for Children, Schools and Families. This was the first time that there was ever a ‘department for the family’ in British politics.

The Government’s aim of this department was to ensure that every child would get the best possible start in life, receiving the on-going support and protection that they – and their families – need to allow them to fulfil their potential. The new Department would play a strong role both in taking forward policy relating to children and young people, and coordinating and leading work across Government and youth and family policy.

Key aspects included:

- Raising school standards for all children and young people at all ages.

- Responsibility for promoting the well-being, safety, protection and care of all young people.

- Responsibility for promoting the health of all children and young people, including measures to tackle key health problems such as obesity, as well as the promotion of youth sport

- Responsibility for promoting the wider contribution of young people to their communities.

Signposting

This post has been written primarily for students of A-level sociology, and is one of the main topics in the families and households module, usually taught in the first year of study.

Related posts include:

- Social policy and the family

- How do social policies affect family life?

- Social Policy and Family Life Summary Grid

To return to the homepage – revisesociology.com

Please click here to return to the homepage – ReviseSociology.com